Shorter title, that contravenes Betteridge’s Law: Is spurring research interest in topic X like Daffy Duck’s magic trick?

Yes, of course you’re going to have to read on to find out what I mean by that! 🙂

***

A few years ago, I asked whether publication of a meta-analysis (or really, any review paper) encourages or discourages publication of further studies on the topic. One could imagine it going either way.

On the one hand, authors of meta-analyses and other review papers often pitch their work as identifying important gaps in the literature, that ought to be filled by future research. And in ecology specifically, meta-analyses tend to find enormous variance in effect size, the vast majority of which reflects heterogeneity–true among-study variation in mean effect size–rather than sampling error (Senior et al. 2016). That implies that ecologists ordinarily will need a lot of primary research papers in order to get reasonably precise estimates of both the mean effect size, and the variance around the mean. They’ll also need a lot of primary research papers to have any hope of identifying moderator variables that explain some of that heterogeneity in effect size. But they don’t usually get a lot of papers. The median ecological meta-analysis only includes data from 24 papers (Costello & Fox 2022). So as Alfredo Sánchez-Tójar suggested in the comments on an old post here, it seems bad if publication of an ecological meta-analysis discourages publication of further studies. We ecologists need all the studies we can get!

On the other hand, publication of a meta-analysis or other review paper usually (not always!) indicates that there are already enough papers on the topic to be worth reviewing/meta-analyzing. Further, meta-analyses and other review papers do ordinarily draw at least some tentative scientific conclusions. Nobody ever publishes a meta-analysis or other review paper for which the only conclusion is “there aren’t enough studies of this topic yet to draw any conclusions whatsoever; everybody please publish more studies!” So it seems only natural if publication of a meta-analysis, or other review, is read by others as a signal that the topic in question is now pretty well-studied. At least, well-studied compared to other topics that haven’t yet been subject to meta-analysis or other review. So researchers who want to do novel work might prefer to avoid working on topics that have recently been reviewed.

On the third hand, most researchers ordinarily have their own future research plans. Those plans usually reflect all sorts of factors. They aren’t ordinarily going to be changed by publication of any one paper, be it a review paper or something else. Especially because any gaps in the literature identified by a meta-analysis or other review probably exist for a reason and so aren’t easily filled. Common example in ecology: a comparative paucity of studies from Africa. Not ideal, obviously–but equally obviously, not a gap that’s likely to be filled just because a meta-analyst calls for future studies to be conducted in Africa. On this view, publication of a meta-analysis or other review won’t have much effect either way on publication of further studies.

As I noted in my old post on this topic, it’s difficult to study causality here, because controlled replicated experiments are impossible. How can you tell how many primary research papers would’ve been published on a given topic, if only a meta-analysis or other review hadn’t been published?

So we’re stuck with the next best thing: eyeballing unreplicated observational time series data and speculating! Which is what I’ll do in the rest of this post. I’ll walk through two case studies in which we have good time series data on the publication of primary research papers on a given topic, extending from well before until well after publication of at least one meta-analysis or other review paper. This is at least a bit of an improvement over time series data I’ve looked at in the past, that only extended up until the publication of a meta-analysis, not after.

The first case study concerns local-regional richness relationships, as a tool for inferring whether local species interactions limit local community membership. Here’s how I summarized the idea in an old post:

The idea is that, by plotting the species richness of local communities against the species richness of the regions in which they’re embedded, you can infer whether local species interactions are strong enough to limit local community membership. Here’s the argument. Species within any local community (a lake, a patch of grassland, whatever) typically didn’t speciate there. Instead, they colonized that local site from somewhere else, presumably from somewhere in the surrounding “region” (the regional “species pool”, if you like). Of course, not all colonists necessarily succeed in establishing a local population. In particular, they might fail because they get competitively excluded by other species. So local species richness reflects both the influence of the surrounding region (the source of colonists), and local conditions that determine the fate of colonists. How can we tease apart the relative importance of regional-scale and local-scale factors in determining local species richness? Why, by going out and sampling the species richness of local communities in different regions, and the richness of those regions, and then regressing local richness on regional richness. If we get a saturating curve (i.e. a curve that asymptotes or seems to be approaching an asymptote), then that means that local communities in sufficiently-rich regions are “saturated” with species. All the niches are occupied and local competition prevents further colonization, setting an upper limit to local richness no matter how many species there are in the regional “species pool”. Conversely, if the local-regional richness relationship is linear, that means that local competition is too weak to limit local community membership. Instead, local communities are just samples of the regional species pool.

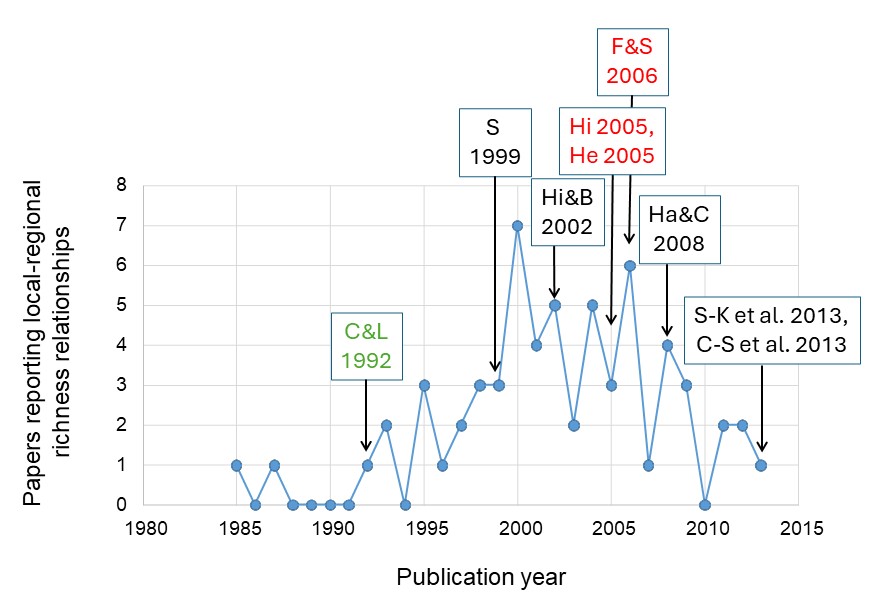

A few different papers in the 1980s suggested ideas along these lines, but the paper that really kicked off interest in local-regional richness relationships was Cornell & Lawton 1992. C&L 1992 is a narrative review/perspective paper. In the wake of C&L 1992, numerous ecologists started publishing local-regional richness relationships, and making inferences from them about the strength of “local” vs. “regional” determinants of local species richness. The topic was both popular enough, and controversial enough, to attract several subsequent reviews (Srivastava 1999, Hillebrand & Blenckner 2002, Harrison & Cornell 2008, Szava-Kovats et al. 2013, Gonçalves-Souza et al. 2013). Some were narrative reviews, others were quantitative meta-analyses. They varied in the degree to which they were critical or supportive of the original C&L 1992 idea, and the degree to which they suggested modifications or refinements of the original idea. Along the way, several ecologists, including me, also published new theoretical work, the broad take-home from which was to undermine the original C&L 1992 idea (Hillebrand 2005, He et al. 2005, Fox & Srivastava 2006). All of these papers were published in widely read, internationally leading journals, and so presumably were noted by most everyone working on the topic.

To figure out the history of empirical papers on local-regional richness relationships, I went back to the two 2013 meta-analyses of local-regional richness relationships (the most recent reviews of the topic). I combined their lists of papers, removed duplicates, and then plotted the number of papers published each year. Here’s the plot, to which I’ve added the publication dates of the various review papers and theoretical papers:

Looking at that plot, I think it’s pretty clear that C&L 1992 did indeed kick off widespread interest in this topic. And if the peak of interest in 2000 doesn’t seem all that high (just seven papers), well, it’s at least a higher peak of interest than for a typical ecological topic that’s later the subject of a meta-analysis.

Now here’s the key question, for purposes of this post: looking at that plot, does it look like any of those later review papers, or any of those theoretical papers, had any appreciable effect one way or the other on the rate of publication of local-regional richness relationships? Because I don’t see much of anything.

In particular, it looks to me like interest was already on the way down by the time I, and others, published theoretical work critical of the basic idea. Conversely, I don’t see any sign that the review of Ha & C 2008, which calls (in part) for further research on the idea, had any success in reviving interest in the idea.

I guess you might speculate that Srivastava (1999) killed off growth of interest in the topic? Srivastava (1999) identified various pitfalls and problems with the local-regional richness relationships available at the time. Srivastava (1999) called the approach a potentially useful tool that should be interpreted cautiously, in conjunction with other lines of evidence regarding local vs. regional determinants of community structure. The publication rate of local-regional richness relationships started falling just over a year later. Maybe because of Srivastava (1999)? I dunno, maybe, but I kind of doubt it. Obviously I’m totally speculating here. But I think it’s at least as likely that interest in publishing local-regional richness relationships would’ve peaked around the year 2000 anyway. The sense that “there’s now a critical mass of papers on this topic” causes some people to write review papers. It also causes other people to go work on some other topic, whether or not a review actually gets published. Some people would rather not jump on a bandwagon that’s already been running for years, whether or not that bandwagon has recently been reviewed. (Or maybe some people do jump on the bandwagon, but only after reframing or relabeling it as something different.)

Or I guess you might speculate that the cumulative effect of Srivastava 1999, Hi & B 2002, Hi 2005, He 2005, and F & S 2006, was to kill off a lot of research interest in this topic? Like, maybe if none of those papers had been published, we’d have ended up with appreciably more published local-regional richness relationships by 2013? Again, I doubt it, but obviously I don’t know for sure.

In any case, it’s definitely hard to look at that plot and argue that Srivastava (1999), or any subsequent review or theoretical paper, appreciably increased the rate at which ecologists published local-regional richness relationships. It just seems really implausible to me to think that interest in this topic would’ve died off even faster, if not for the publication of all those reviews and theoretical papers in the 2000s.

So I think this case study cuts against one of our three hypotheses: that meta-analyses and other review papers increase the subsequent rate of publication on the topic (e.g., by identifying gaps in the literature that need filling, or by suggesting refined study designs that future studies ought to adopt). But what do you think?

Now let’s turn to our second case study: metacommunity variance partitioning. Cottenie (2005) proposed that, if you had data on species abundances and key environmental variables at each of many sites, and data on the geographic distances among those sites, that you could use a statistical technique known as variance partitioning to infer the drivers of metacommunity structure (i.e. the drivers of variation in species composition and abundance among sites). Cottenie (2005) illustrated the proposed approach by applying it to many published datasets originally collected for other purposes. In the wake of Cottenie (2005), many ecologists published metacommunity variance partitioning studies. Soininen (2014) published a meta-analysis covering both Cottenie’s datasets and the studies that applied Cottenie’s approach through 2012. (Aside: Soininen 2016 is a second review paper based on the same data compilation as Soininen 2014.) Recently, Lamb (2020; unpublished MSc thesis) updated Soininen’s 2014 meta-analysis by incorporating additional studies published from 2013 to (I presume) 2019. I presume 2019, because it seems most likely to me that an MSc thesis defended in 2020 would’ve completed data compilation in 2019. But whatever; nothing I’m about to say is sensitive to exactly when Lamb (2020) completed data compilation. Lamb (2020) found 50 metacommunity variance partitioning papers published from 2013 thru (I presume) 2019, an average of just over 7 papers per year. Lamb (2020) unfortunately doesn’t list those 50 papers or their publication dates. But for back-of-the-envelope guesstimate purposes, let’s assume that the number of metacommunity variance partitioning papers published per year exhibited a linear trend over time. So here’s a graph of the number of metacommunity variance partitioning papers published annually from 2006-2012 (blue points, solid line), and what a post-2012 linear trend would have to look like in order to result in 50 additional publications from 2013-2019 (black points, dashed line). You can see the rapid growth in publication rate up to a peak in 2011 (blue points, solid line), followed by an apparent decline:

Obviously, I don’t think that hypothesized linear trend exactly matches the real post-2012 trend. In particular, one might wonder if the publication rate stayed comparatively high in 2013-14, and then dropped more steeply after publication of Soininen (2014). But the bottom line is that, post-2012, there was an average of about 7 metacommunity variance partitioning papers published per year. Maybe a bit more or less than that, depending on exactly when Lamb (2020) completed data compilation. But whatever the true post-2012 average is, it’s less than the number of metacommunity variance partitioning papers published in the peak year (11 papers in 2011). Indeed, the true post-2012 annual average seems likely to be at least slightly less than the number of metacommunity variance partitioning papers published in any year from 2009-2012.

Now, I suppose one could argue that the publication rate of metacommunity variance partitioning papers would’ve dropped even more over time, had Soininen (2014) not been published. Maybe! But it’s more plausible to me that Soininen (2014) either had no effect on, or reduced, the post-2014 publication rate of metacommunity variance partitioning papers.

It’s perhaps worth noting that, as with the local-regional richness case study, there’ve been several theoretical and review/perspectives papers questioning whether metacommunity variance partitioning actually allows you to infer the drivers of metacommunity structure (Gilbert and Bennett 2010, Smith and Lundholm 2010, Logue et al. 2011, Brown et al. 2016). And as with the local-regional richness case study, it’s perhaps notable (or perhaps merely a coincidence) that publication rate of metacommunity variance partitioning papers seems to have peaked about a year after the publication of the first paper(s) that were at least somewhat critical of the approach. I didn’t put these other papers on the graph, because it seemed like overkill given the limited post-2012 data. But I wanted to note them.

So in summary then, I think it’s difficult to eyeball these data and see any sign that meta-analyses or other review papers increase subsequent research effort on a topic. It looks to me like they either have no effect, or maybe decrease subsequent research effort. Spurring empirical research interest in a topic seems like Daffy Duck’s magic trick: it can only be done once:

🙂

These are just two case studies. Do the results generalize? I don’t know, but if I had to guess, I’d say yes. In an old post, I looked at data from a bunch of ecological meta-analyses, suggesting that publication rate on a given topic typically peaks a year or two before publication of a meta-analysis. In response, Brian suggested that I was wrong–that those apparent peaks typically are artifacts of meta-analyses omitting studies published shortly before the meta-analysis. Brian had a good point. But nevertheless, these two case studies make me think I was mostly right in that old post. I think publication of the first meta-analysis on a given topic usually marks the peak of research interest in that topic, give or take a year or two in either direction. Whether or not it actually causes the peak.

In the comments, discuss: what, if anything, do these very tentative results imply about calls for future research in meta-analyses and other review papers? Particularly calls to fill gaps in the literature–that we need more studies of topic X in Africa, or in invertebrates, or in aquatic systems, or in urban areas, or whatever. Should meta-analysts and other review authors not bother with such calls for future research, because those calls are likely to fall on deaf ears? Or are there other reasons to make such calls, even though they’re unlikely to have much effect on future research? Or what? Looking forward to your thoughts. Personally, I feel like calls for future research to fill gaps in the literature are pointless. They’re just empty gestures that (presumably) make the authors feel good, but don’t actually accomplish anything.* But what do you think?

p.s. If anyone knows of other cases in which the same topic was reviewed more than once over a period of several years, by all means pass them on! It would be good to have more than two case studies. I already thought of the case of field experiments on interspecific competition. But that’s a difficult case to use, because three key reviews/meta-analyses (Connell 1983, Schoener 1983, Gurevitch 1992) all used quite different inclusion criteria. So it’d be hard to use those reviews/meta-analyses to construct a single unified time series of published field experiments on interspecific competition.

*What percentage of calls to fill gaps in the literature get filled by the authors who called for the gaps to be filled? I bet it’s pretty low. Which, if so, is a small illustration of the fact that gaps in the literature, while undoubtedly real and unfortunate, mostly exist for reasons that we cannot address at all merely by calling attention to them in meta-analyses and other review papers.