LONDON — SpaceX’s Starship will be a game changer for space-based solar power generation and will make orbiting power plants not only affordable, but cheaper than many other methods of generating electricity on Earth, according to Michigan-based start-up Virtus Solis.

Virtus Solis, founded by former SpaceX rocket engineer John Bucknell, introduced their solar power beaming concept at the International Conference on Energy from Space held in London on Wednesday, April 17.

“For space-based solar power to work, you need to have heavy-lift launch, you need to have wireless power transfer and you need to have the economics,” Bucknell said at the conference. “Once you have low-cost access to space, that’s one less miracle that you need to have solved.”

Related: Space-based solar power may be one step closer to reality, thanks to this key test (video)

The cost of launching satellites to space has plummeted in recent years thanks to the advent of reusable rockets pioneered by SpaceX. The company currently charges under $3,000 per kilogram of payload, but that’s still too much for space-based solar power generation, which will require enormous orbiting arrays larger than the world’s largest currently orbiting object, the International Space Station.

SpaceX promises that once Starship is fully up and running, it will cost as little as $10 per kilogram to loft satellites to space. Although that estimate might be a little too optimistic, Bucknell says that once the cost of launch into low Earth orbit falls below $200 per kilogram, space-based solar power will become cheaper than Earth-based nuclear plants or gas and coal-fired power stations.

“Once Starship is fully reusable, that will drive down the cost,” said Bucknell. “SpaceX has recently flown a Falcon 9 booster for the 20th time and they are recertifying for 40 launches. Conceivably, Starship could do hundreds of launches. But we are basing our assumptions on a 15-times use.”

Currently, Earth-based photovoltaic panels provide the cheapest source of electricity at less than $30 per megawatt-hour. But the sun doesn’t shine at night, and energy experts struggle to make up for that daily drop with other renewable sources. So far, nuclear, gas and coal-fired plants need to be on standby to cover the demand after dark or in bad weather. But gas and coal need to be phased out for the world to meet its emission reduction goals.

And nuclear power, Bucknell said, is much more expensive. “The cost of nuclear power is between $150 and $200 per megawatt hour,” said Bucknell. “We think that our system could get down to around $30 per megawatt hour once at scale.”

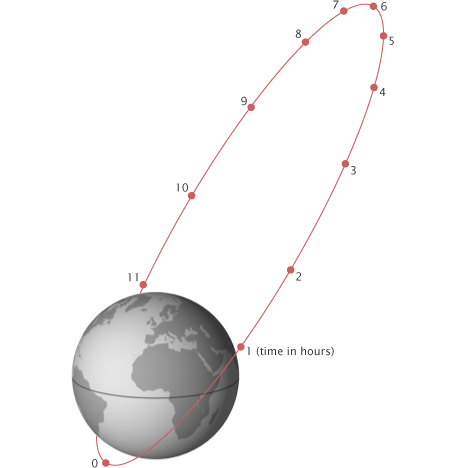

Virtus Solis wants to build giant photovoltaic arrays up to 0.6 miles (1 kilometer) across that would be assembled in orbit by robots from 5.3-foot (1.6 meters) wide modules. Hundreds of such modules would be delivered by a single Starship into the Molniya orbit, a highly elliptical orbit with the closest point about 500 miles (800 km) above Earth and the farthest at 22,000 miles (35,000 km).

A satellite in this orbit takes 12 hours to complete one lap around the planet, but the nature of this orbit is such that the spacecraft stays for more than 11 hours in the most distant region from where it can view nearly an entire hemisphere.

A constellation of two or more such arrays would therefore provide constant “baseload power” to a region, said Bucknell. A system of 16 arrays would cover the entire world, beaming energy in the form of microwaves to giant receiving antennas on the ground.

Bucknell said the company is now working on improving the efficiency of wireless power transmission, which is another major stumbling block for space-based solar power. Current systems have efficiencies of around 5 percent but for practical use, efficiencies of around 20 percent will be needed.

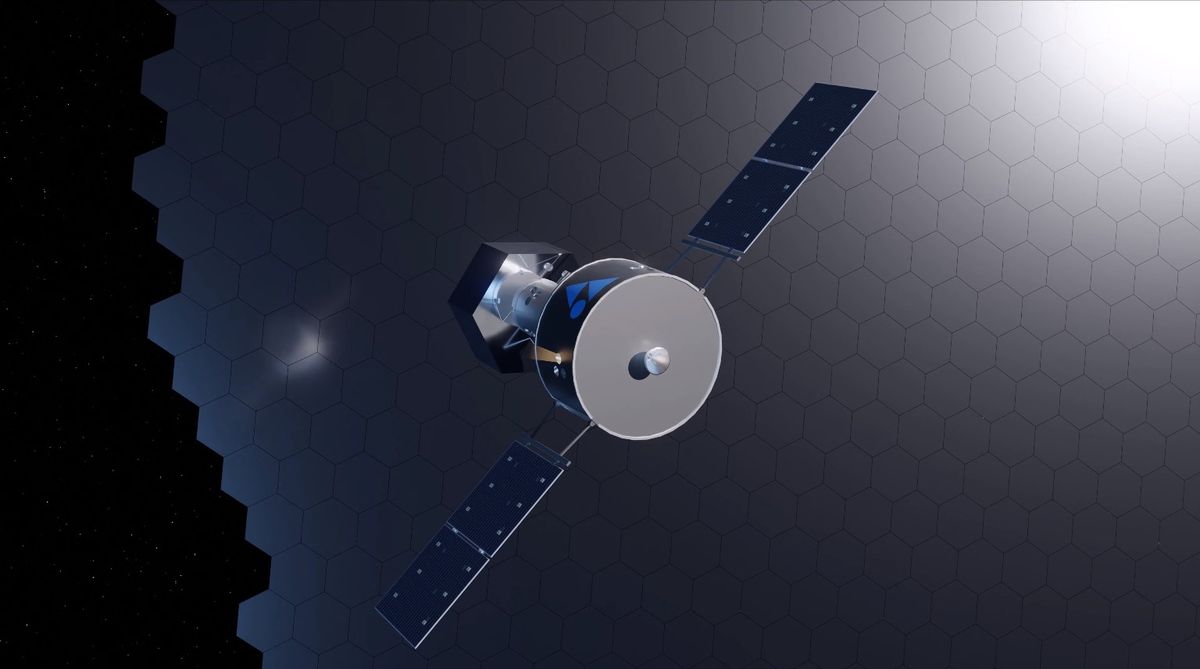

In February, Virtus Solis announced plans to launch a demonstration power-beaming satellite in 2027 that would test in-space assembly of solar panels and transmit more than one kilowatt of power to Earth, according to Space News. The firm hopes to build a commercial megawatt-class solar installation by 2030.