A few years ago, I compiled data on the number of applicants for tenure-track ecology faculty positions in North America, and had some fun building an exploratory statistical model that predicted which jobs would get more applications. I did this just out of curiosity. The answer was basically that jobs at R1 unis, jobs in the Pacific Northwest, and jobs near the East Coast tend to get the most applicants, while fish & wildlife jobs tend to get the fewest applicants.

That analysis had some limitations. It was based on a dataset of just 86 jobs for which I was able to determine the exact number of applicants with high confidence. And some of the predictor variables were difficult to interpret, because they were crude surrogates for various intercorrelated variables that likely figure into the decision-making of at least some ecology faculty job seekers. For instance, US colleges and universities close to the coasts are disproportionately likely to be located in urban areas, in well-off areas, and in politically “blue” (meaning “left of center”) states. So was the longitude of the hiring institution (one of my predictor variables) best thought of a surrogate for urbanization, or economic well-being, or the political orientation of the state, or all of the above, or what?

To get a more refined sense of what factors loom largest in ecology faculty job seekers’ decisions as to where to apply, I turned to a different, much larger data set.

As most of you know, the annual ecoevojobs.net Google spreadsheet provides a near-comprehensive list of faculty positions and other permanent PhD-level EEB jobs in the US, plus less-comprehensive coverage of other countries. The spreadsheet includes a column called “number applied.” If you’re an ecoevojobs.net user, and you want to report that you applied for job X, you increase the “number applied” count for job X by 1. Of course, only a small minority of applicants for job X are likely to record their applications in the “number applied” tab on ecoevojobs.net. But I showed in the post linked to above that the “number applied” count is an unbiased (albeit quite imprecise) index of the true number of applicants. So I decided to look at some predictors of the “number applied,” to get a sense of the collective preferences of EEB faculty job seekers.

I say “EEB” rather than “ecology” because, for this analysis, I used all the US jobs on the ecoevojobs.net spreadsheet, rather than culling all the non-ecology jobs as I have in past analyses. I used all the US EEB jobs in order to maximize sample size. I used only the US jobs, not the non-US jobs, in order to focus on US-related predictors of the number of applications. I kept all the permanent jobs, as opposed to just the faculty jobs, in order to maximize sample size. So the dataset includes some government, NGO, and non-faculty academic jobs, although it’s mostly tenure-track faculty jobs. The dataset does not include postdocs, visiting assistant professor jobs, lab manager jobs, or other non-permanent jobs. I used data from 2018-19 up through 2023-24, inclusive. I cleaned the data by dropping a handful of jobs for which the number of applicants was a non-numeric value (such as the letter f or an emoji), or an implausible or impossible numeric value (such as a negative number). I treated blanks as zeroes, because the “number applied” counter starts blank, and gets incremented to 1 by the first ecoevojobs.net user who reports applying for the job in question. I ended up with 4458 permanent US EEB jobs in total, which is a lot.

I calculated the mean and median number of applicants/job for each state, in order to focus on three state-level predictors of the mean and median number of applications per job. I used state-level averages/medians, and state-level predictors, because it would’ve been a pain to compile more fine-grained predictors (say, county-, city-, or institution-level) for every job, and it would’ve been overkill to build a hierarchical mixed effects model. My state-level predictors were:

- Nate Silver’s index of urbanization. It’s the ln-transformed number of people who live within 5 miles of the average resident of each state, as of the 2020 US Census. As Silver’s linked post discusses, “urbanization” is a tricky, scale-dependent concept, but this index seems to do a reasonable job of capturing the degree to which a state’s average resident experiences an “urban” environment in their day-to-day life. For instance, most of Nevada has no people living in it at all. But yet most residents of Nevada experience it as quite an urban place, not a rural place. That’s because a substantial fraction of everyone in Nevada lives in one of two big cities (Las Vegas and Reno), the biggest of which (Las Vegas) is fairly dense. Conversely, states like Wyoming, Utah, and New Mexico also have lots of people-free space–but the cities in which most people in those states live aren’t all that big or dense. So the average person in Wyoming, Utah, or New Mexico has many fewer people living within 5 miles of them than does the average person in Nevada.

- Joe Biden’s vote share in the 2020 US Presidential election (percentage of all votes cast that went to Biden), as a measure of the political lean of the state.

- Median household income as of 2019, from the American Community Survey, as a measure of how well-off the typical household in the state is economically.

Now is probably a good time to emphasize that I’m not doing rigorous social science here. I chose my candidate predictors pretty haphazardly, out of a mix of convenience and personal curiosity. I’m well aware that these predictors will be correlated with one another, and with other predictors I haven’t considered. There are many analyst degrees of freedom here! Everything I’m about to say is best thought of as some combination of description, exploration, and hypothesis generation. Not hypothesis testing.

Here’s what I found. First, a sanity check: the number of EEB jobs per state covaries tightly and linearly with state population as of 2020, as you’d expect it to (R^2 = 0.89, with no big outliers or obvious nonlinearity). The dataset includes 10 EEB jobs in Wyoming, up to 409 in California. And as you’d expect, there’s substantial state-to-state variation in mean and median number of ecoevojobs.net users who reported applying to permanent EEB jobs. The mean ranges from a low of 0.5 applicants/job in West Virginia, up to a high of 7.7 applicants/job in Vermont. The median ranges from a low of 0 applicants/job in West Virginia, Mississippi, and Missouri, up to 4 in Oregon and Connecticut.

In bivariate scatterplots, all three predictors are positively associated with both mean and median number of applicants. That is, permanent EEB jobs in bluer, more urbanized, more well-off states tend to attract more applicants. And of course, all three predictors are positively correlated with one another to varying degrees. None of that is surprising, though it’s reassuring to see it confirmed. It’d have been worrisome if those bivariate analyses hadn’t come out that way.

I tried to tease apart these three predictors by chucking them all into a linear model for mean number of applicants. I was surprised that only Biden vote share came out significant in Type III SS (meaning, it’s the only predictor for which dropping it from the full model significantly reduced the fit). And in a Type I SS ANOVA, Biden vote share always came out significant, no matter the order in which the predictors entered the model. Whereas the other two predictors only came out significant if they entered the ANOVA before Biden vote share. Indeed, any other predictor that entered the ANOVA after Biden vote share ended up with a trivially tiny SS. That is, Biden vote share captured essentially all of the variation in the mean # of applications that was captured by both of the other predictors, plus substantial additional variation. The residuals for the full model looked good, except that Washington DC was an outlier. Finally, the variance inflation factors weren’t nearly big enough to be a serious concern–these three predictors are intercorrelated, but they’re not all that intercorrelated.

It’s a broadly similar story if you look at median number of applications rather than the mean. In an ANOVA with Type I SS, Biden vote share comes out significant as long as it’s not the last predictor to enter the model. Whereas the other two predictors only come out significant if they enter the model before Biden vote share.

Here’s a scatterplot of the mean number of applications per job reported by ecoevojobs.net users, vs. Biden vote share in 2020. The outlier on the right-hand side is Washington DC. Biden vote share in 2020 explains 41% of the variance in the mean number of applications per job.

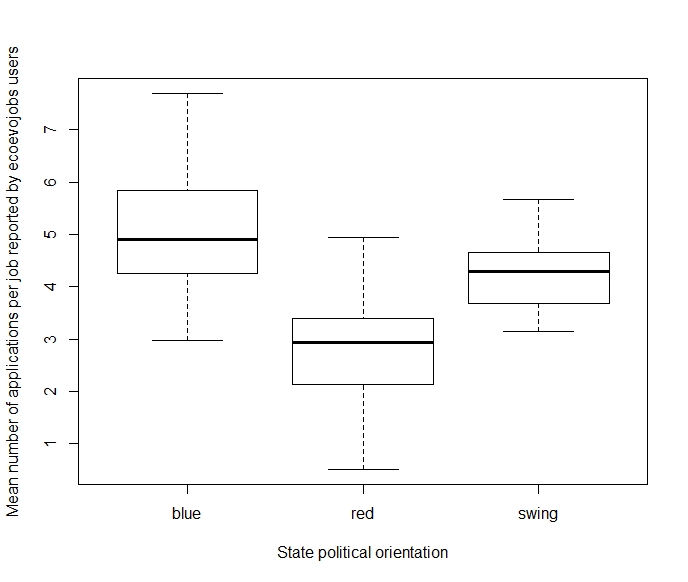

In fact, you can do even better if you replace Biden vote share in 2020 with a three-level categorical variable: is the state a blue state, a red state, or a swing state. “Swing” states are Arizona, Nevada, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Michigan, Georgia, and North Carolina. That three-level categorical variable explains 50% of the variance in the data. Which is actually the bulk of the 81% of the variance in the data that you can explain by categorizing states into three groups so as to maximize between-group variation and minimize within-group variation (i.e. k-means clustering with 3 groups). Here’s a boxplot:

These results surprised me. I expected urbanization to be the best predictor of number of applications to EEB jobs reported by ecoevojobs.net users. I thought that, compared to the other predictors of where EEB job seekers apply, urbanization would be a stronger correlate of more factors, that matter more, to more EEB job seekers. I was wrong. But maybe I shouldn’t have been surprised? I mean, obviously, state laws and policies related to higher education are going to have a big effect on your life as an academic. Other state laws and policies are going to have a big effect on your life whether you’re an academic or not. So maybe it’s not so surprising if many EEB job seekers are deciding where (not) to apply in large part based on political considerations.

Then again, these data don’t necessarily show that political considerations per se are the overriding consideration for most EEB job seekers when deciding where to apply. State political orientation only explains 50% of the variation in mean # of applications/job, not 100%. Further, state political orientation is correlated with various variables besides the other two that I measured, that might plausibly matter to at least some EEB job seekers.

For instance, in this dataset it’s clear that ecoevojobs.net users, as a group, don’t just want to live in any ol’ blue state. They want to live in New England. Or failing that, California. The top six states by mean number of applications per permanent EEB job are Vermont (mean 7.7), Massachusetts (6.9), Connecticut (6.9), Rhode Island (6.7), California (5.9), and New Hampshire (5.8). Maine is only a bit further down the ranking list (15th; mean 4.7 applicants/job). Yes, those states are politically blue–but so are many other states that don’t draw nearly as many applications to permanent EEB jobs. So I suspect that two of the unmeasured variables for which state political orientation is an imperfect surrogate are “Is it a job in New England?” and “Is it a job in California?” There are of course various reasons why many EEB job seekers might apply to jobs in New England or California. For instance, some unknown-but-not-trivially-small fraction of ecology faculty job seekers seem to conduct geographically restricted job searches. One possible hypothesis is that for some (many?) EEB job seekers, jobs in New England and California combine political congeniality with geographic proximity to family and friends (and presumably other desirable features in some cases). Maybe what’s going on here is basically the EEB version of The Big Sort.

The result that permanent EEB jobs in New England tend to draw the most applications from ecoevojobs.net users is an interesting contrast to the results of my previous analysis of applicant count for 86 ecology faculty jobs. In that analysis, the Pacific Northwest came out as the most popular geographic region. On the other hand, California, Oregon, and Washington all rank pretty high in terms of mean number of applicants per permanent EEB job in this dataset, so the contrast with my previous analysis isn’t all that big.

Conversely, where don’t ecoevojobs.net users prefer to apply? To permanent EEB jobs in states that are both very politically conservative and very rural. The bottom five states by mean number of applications per position are West Virginia (mean 0.5 applications per job), South Dakota (1.2), North Dakota (1.4), Arkansas (1.7), and Mississippi (1.8). That’s close to (though not quite) a list of all and only the US states that are both very politically conservative and very rural. Oklahoma and Alabama also are both very politically conservative and very rural, and they rank only slightly higher in terms of mean number of applications per position (respectively 8th and 10th from the bottom, with means of 2.1 and 2.6 respectively). The only two very rural + very conservative states that draw a reasonably high number of applicants on average to their permanent EEB jobs are Wyoming (4.1) and Kentucky (4.9). In the case of Wyoming, I wonder if that comparatively high mean is just a blip, because there are only 10 Wyoming jobs in the entire dataset. But I’m very surprised that permanent EEB jobs in Kentucky draw so many applications on average. There are 38 Kentucky jobs in the dataset, so that mean isn’t just a small sample blip (is it?). And it’s not that the mean was pulled way up by one or two Kentucky jobs that drew a bunch of applications. The median number of applicants for permanent EEB jobs in Kentucky was 2, an intermediate number in this dataset, and higher than the medians for West Virginia, the Dakotas, Arkansas, and Mississippi (all 1 or fewer). 82% of Kentucky jobs drew at least one applicant. That 82% is one of the highest such percentages for any state in the dataset. In contrast, only 41% of West Virginia jobs drew at least one applicant. Permanent EEB jobs in Kentucky seem to draw appreciably more applications on average than permanent EEB jobs in (say) Minnesota, Michigan, Maryland, Delaware, Georgia, Florida, or Texas! I have no idea what’s up with that.

Speaking of things with which I don’t know what’s up…why do permanent EEB jobs in Minnesota draw so few applications (mean 3.0, median 1, only 56% drew any applications at all)? Minnesota is politically blue, it’s comparatively well-off in terms of household income, and it’s roughly average in terms of urbanization. Plus it’s home to a giant R1 university that’s known for its strong EEB department.* I have the same question for Michigan and Maryland: both states that would seem to tick a lot of boxes for a lot of EEB job seekers, but whose permanent EEB jobs don’t attract all that many applicants on average (means of 3.1 and 3.3 applicants/job, respectively). I’d have thought every EEB job seeker would want to live near Meghan! 🙂 I was also surprised by Alaska, which draws a mean of 3.0 applicants/job despite being fairly politically conservative, extremely rural, extremely cold, and extremely remote. Maybe Alaska’s remoteness is a plus for a minority of EEB job seekers? But I dunno, maybe all this is just me puzzling too much over individual observations. If your predictor variable only explains 50% of the variance in the dependent variable, then by definition there are going to be some observations that are pretty far from their predicted values, for reasons that the GLM will be unable to explain.

One takeaway from this exercise is that there are a fair number of permanent EEB jobs in the US that don’t attract many applicants. Even in the most popular states, 15-20% of permanent EEB jobs receive no self-reported applications from ecoevojobs.net users. In the least popular states, roughly half of permanent EEB jobs receive no self-reported applications from ecoevojobs.net users. Now, as an EEB job seeker, I’m not sure what you can do with this information. I mean, there’s no point to applying for a job that you definitely wouldn’t take, just because few others are likely to apply. Nor would it make any sense to pass on applying for a job you’d definitely take, just because many others are likely to apply. But if you’re unsure or on the fence about whether you’d take the job, maybe the likely number of applications is one factor to consider, among others? A line of thought like “Taking a permanent job in [less popular state] wouldn’t be my first choice, but it’d be better than another postdoc, I wouldn’t have to stay there forever, and at least I’d probably be competing against fewer applicants” seems like a pretty reasonable line of thought to have, at least for some EEB job seekers. (YMMV on whether this line of thought is a good fit for you personally, obviously.)

One caveat to everything I said in this post: I don’t know if or to what extent ecoevojobs.net users who use the “number applied” counter are representative of EEB job seekers as a whole, in terms of their preferences as to where to apply. I could easily imagine that they’re representative–and easily imagine that they’re not (e.g., because they care more about state political orientation than the typical EEB job seeker). I just have no idea. Ok, I doubt they’re very unrepresentative. But they might be somewhat unrepresentative.

A second caveat to everything I said in this post: there’s a lot of variation in number of applications among jobs within states. Don’t forget that just because I focused on predicting state-level means and medians in this post.

In conclusion, a reminder, in the unlikely event that one is needed: this post is descriptive not prescriptive. I’m just curious about the collective decision-making of my fellow EEB folks. I’m not out to praise or condemn any EEB job seeker’s reasons for applying, or not applying, to jobs in a particular state. People should apply where they want to apply. And if they sometimes end up passing on applying for a job they’d actually have liked if they’d gotten it (say, because they mistakenly think they wouldn’t like living in Minnesota or whatever), well, that’s just life in a world where nobody has a crystal ball.

Looking forward to your comments, as always.

*Back when I was on the EEB job market, I was thrilled to get a campus interview at the University of Minnesota, and would’ve been equally thrilled to interview at Carleton, Macalaster, or St. Olaf’s. I dunno, did that make me a bit atypical?